A friend of mine has moved to a beautiful old craftsman style-cottage in Port Townsend with a landscape full of edible plants. The other day a fragrant scent greeted me as I opened the gate. I turned down the side brick path before knocking on the door.

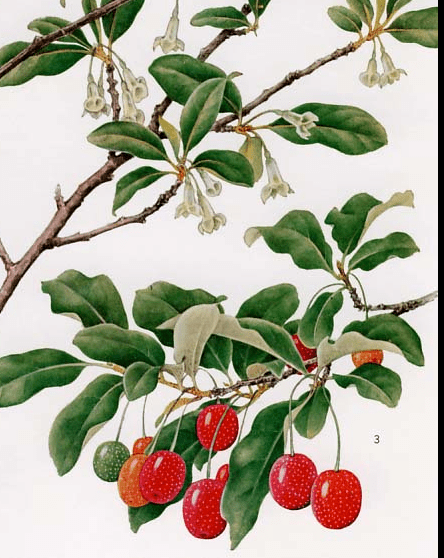

Was it coming from the flowering shrub with an abundance of pale-yellow tubular flowers? The shrub was humming with bees and other pollinators. What was it? The bronze colored scale on the tender stems made me think of Elaeagnus, the genus including Autumn Olive and Silverberry. But so many flowers! Compare the photo to the botanical illustration of the species below.

Knowing this was an edible landscape, my mind flashed to an unusual deciduous shrub I knew from a garden I once tended in the late 1990’s. What was the name-goji? No, but something like that. The scarlet berries dangled from stems tantalizing me. In late summer I popped them in my mouth to savor the astringent sweet-tart flavors. The longer they were left unpicked the sweeter they became, that is if the birds didn’t get them first.

But the shrub I remembered was never wreathed in blossoms. The flowers were sparse. The shrub was growing on the edge of the garden next to blueberries, rhubarb, and Abronia. The client had gotten the plants from One Green World Nursery. I remember reading their catalog that promoted Mountain Ash, Sea Buckhorn, and other ornamentals that plant breeders in Russia and and Ukraine had been selecting for larger, more delicious fruits. The Oregon nursery owners had gone on plant expeditions to bring back edible crops.

QUICK FACTS

- Soil: flexible, variable pH

- Water needs: drought tolerant once established

- Pest: disease and pest resistant. Protect trunks from girdling by rodent

- Height: 6 to 9 feet

- Foliage: deciduous silvery green

- USDA hardiness: Zones 5-9

- Medicinal: Lycopenes help prevent heart disease.

- Propagation: Species by seed from ripe seed. Varieties by softwood cuttings with a heel in July/ August or hardwood cuttings from current year’s growth or and layering.

- Cultivars: Sweet Scarlet™, Ukranian variety self-fertile but best when cross-pollinated with Red Gem™. Note trademark means plants are patented and cannot be propagated for commercial production!

Elaeagnus multiflora, an Asian native has been cultivated in the US for many years. LH Bailey, one of my horticultural heroes discusses it in The Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture in 1927. It is native to Japan where it is known as natsugumi. There it grows into a small tree. Other edible Japanese natives in the genus include Aki-gumi, E. umbellate, known here as Autumn Olive. The fruits of this shrub are high in lycopene, so goumi may be too. Unlike Autumn Olive goumi is not invasive.

Nawashiro-gumi, E. pungens.

But this shrub was not a random seedling, but a named variety, grown from cuttings, I’m sure of it. Plant breeders have bred it to produce more flowers. Compare the photo of my friend’s plant with this botanical illustration:

Landscape and Permaculture Use

This drought tolerant, deer-proof and pest-free shrub offers a special bonus; nitrogen fixing. Elaeagnus form symbiotic relationships with bacteria called actinomycetes that form nodules on the shrub roots and fix nitrogen from the air. This characteristic is found in some plants that are the first to colonize disturbed sites. These pioneer plants can grow in poor soils and enrich the soil.

Taking a cue from nature, the permaculture design approach uses Elaeagnus as an early succession plant. Consider planting it in a windbreak of tough plants in poor soil and five years later remove some replacing them with plants that require more fertile soil.

Potential Crop Production

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin are exploring the potential for a commercial market for goumi. Planted in organic systems it can be grown like other hedgerow fruit crops like gooseberry, elderberry, serviceberry, and cornelian cherry. Plant them 4 feet apart and prune into multi trunk shrubs that are allowed to branch about two feet high and maintain at five or to six feet, so it can be mechanically harvested.