Last week I visited a small, artisanal palenque in Santiago Matatlán that has been a family operation for many generations. I had the opportunity to visit because my Spanish tutor in Teotitlan del Valle knew them. In fact, they supply her family’s store and had invited her to come tour their operation. Matatlán is referred to as the Mezcal Capital del Mundo because over one hundred small-scale producers grow and make mezcal.

Sign on the roadside claiming Matlan as the Mezcal Capital

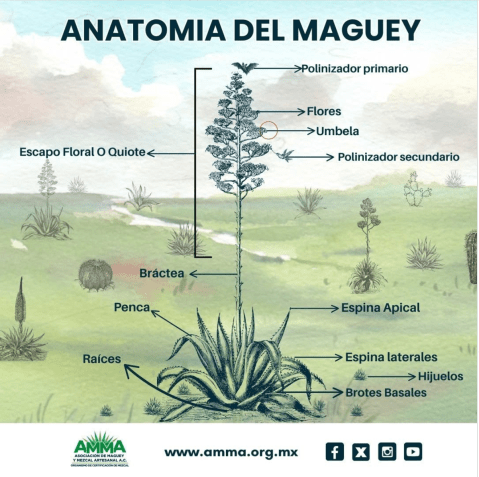

Nereo explained that agaves, in nature only flower after many years. Once enough sugars and juices are concentrated in the heart of the plant, it sends up a tall shoot adorned with flowers. After seeds mature, the entire plant dies. In cultivation, the agave or maguey is harvested right before flowering.

Harvesting

Mezcaleros want the sweet juices at the core of the plant so they walk the rows to select agave plants with an emerging flowering stalk or quiote. Harvesting the plant is done by hand—leaves are chopped off with a machete, leaving the core or the piña—called that because it looks like a pineapple.

Nereo’s grandson harvesting Espadin plants.

It takes 6-15 kg of piña and 10 liters of water to distill 1 liter of mezcal

Espadin piña

Tobala piña delivered by truck from the wild.

Roasting

Once they have enough piñas, the mescaleros start the roasting procedure. Unfortunately, I have not watched this process, but I think a fire is started in the pit with oak or mesquite, then covered with volcanic rocks that turn bright red. Next the piñas are placed in a heap and covered with agave foliage or burlap sacks. Volcanic rocks absorb more smoke so the roasting agave aquire less smoke flavor. Apparently in different regions a slight smoke flavor is valued and other rocks are used. Nereo said that a smokey flavor is undesirable. The roasting process is monitored for 3-5 days.

Mashing piñas

When the piñas are removed, they are brown, caramelized, sweet and stringy. (Since Nereo didn’t have a current batch, the below photo is from Don Agave’s pulque, located across the highway from Teotitlan del Valle.)

The roasted piñas are then mashed in the traditional stone mill pulled by a single horse.

Fermentation

The maguey mash is forked out, carted to oak tanks, where water is added and it’s allowed to ferment for two weeks. Over the years, these tanks acquire natural yeast residue that assists with the conversion of agave sugars and juice into alcohol.

Distillation

The fermented liquid is poured into a traditional still consisting of masonry ovens, copper tubes, clay pots heated from below by a wood fire. Water cools the pipes causing the alcohol vapor to condense back to liquid. the flowing water absorbs heat. A constant stream of water through the condenser ensures efficient cooling.

Nereo’s other grandson pouring the fermented liquid into the still, to begin distillation.

Angelica Mendoza asking about the distillation process.

Water cools the pipes causing the alcohol vapor to condense back to liquid. The flowing water absorbs heat. A constant stream of water through the condenser ensures efficient cooling.

The alcohol emerges from below the last brick tank. The spigot at the base is just barely visible.

We enjoyed sampling the joven mezcal!